He is outside of language and outside of difference. He has been exposed to none of those divisions by means of which the cultural subject is constituted ―self/other, male/female, unconscious/preconscious, need/desire- and is therefore incapable not only of speaking or thinking, but of hearing, seeing, dreaming or experiencing a sense of lack. Kaspar’s condition in the cave corresponds to what Freud calls the “oceanic self” or what Lacan refers to as “l’hommelette” he is a human “egg” spreading in all directions, unshaped as yet by any limitations or boundaries. I believe it is possible to offer an similar diagnosis from other perspectives as well: In an essay she wrote about Herzog’s film back in 1981, art historian Kaja Silverman offer a psychoanalytical reading of his condition. In this sense, Kaspar Hauser’s “rehabilitation” into humanity could understandably be experienced as an abrupt fall.

In the latter, this ordeal is intimately associated with knowledge or, more precisely, with the ability to make distinction (which is very precisely the function of critical thinking in the etymological meaning of the word).

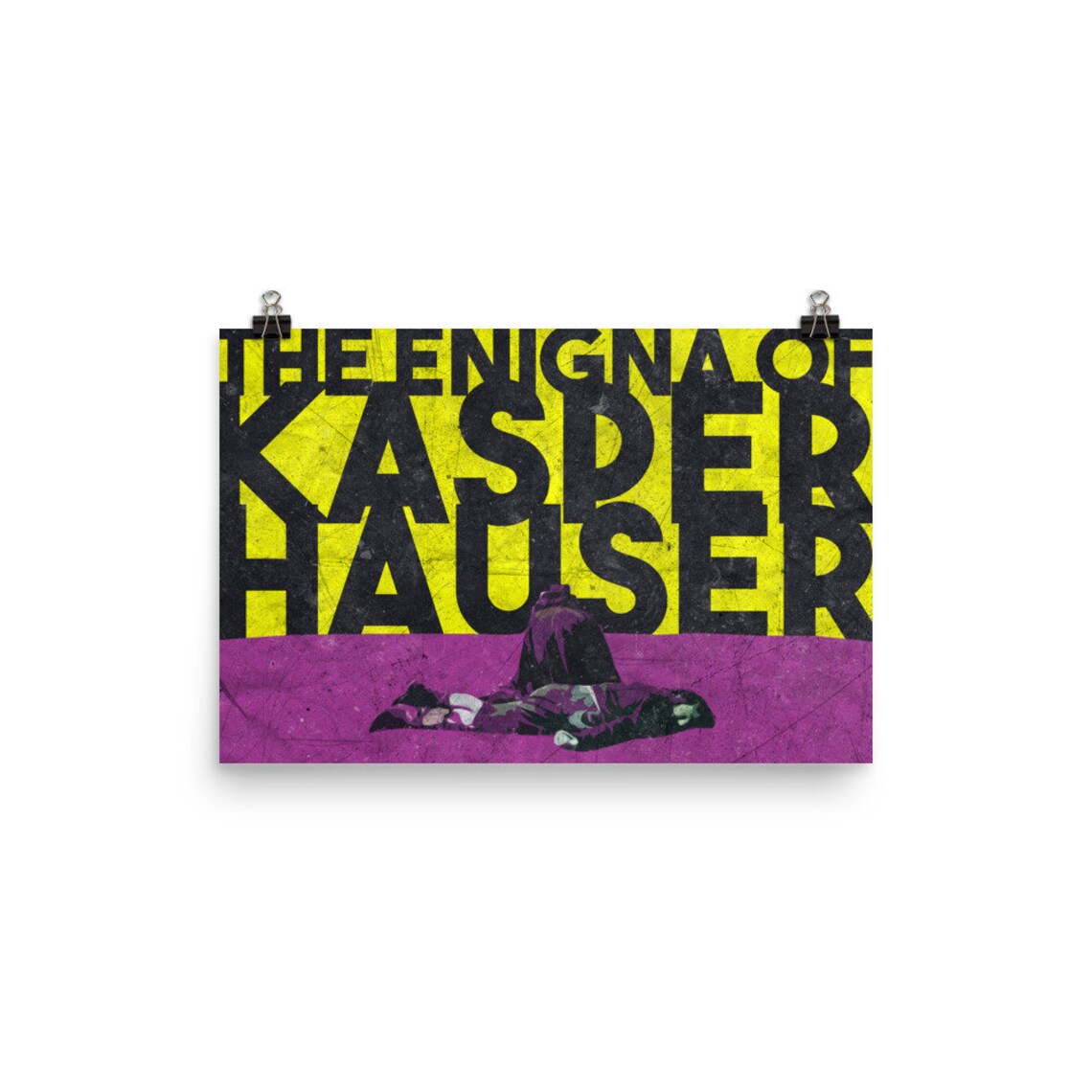

The description of the tumultuous and harsh process of coming into the world can be found both in Hesiod’s Theogony and in biblical narratives (the concept of the “fall of man” is treated in Genesis, chapter 3). ( Journal of Analytical Psychology, Volume 39, Issue 2, April 1994, p. This does not result from spatial proximity to the excreta or from the negativity of a renunciation of sexual activity the feeling directly corresponds to the destructive component of the sexual instinct. The joyful feeling of coming into being that is present within the reproductive drive is accompanied by a feeling of resistance, of anxiety or disgust. This psychological aspects associated with this view were investigated in Sabina Spielrein’s fundamental essay “Destruction as the cause of coming into being” (first published in 1912): The actual act of creation could be said to be much more ambiguous and tormented, intrinsically associated with processes of de-creation. We tend to see such an event ―coming to life, coming to this world: birth, etc.― as something miraculous, magical and/or beautiful (thus the shocked reaction in the film of his guardian Herr Daumer). Kaspar Hauser’s interpretation of his coming into being runs contrary to some common narratives. was told by the real Kaspar Hauser– if we are to believe a comment made by Werner Herzog in the book Herzog on Herzog:Īre any of the lines that Kaspar speaks taken from the autobio- graphical fragment he wrote?Ī few are, like the text of the letter found in Kaspar’s hand that is read by the cavalry captain, and Kaspar’s own very beautiful line, ‘Ja, mir kommt es vor, das mein Erscheinen aufdieser Welt ein bar- ter Sturz gewesen is?. This line is apparently authentical –i.e. Either way, it is an unmissable film.☛ The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser ( Jeder für sich und Gott gegen alle) by Werner Herzog, 1974. But perhaps now in the era of the Fritzl case – and its various fictional treatments – our attention turns to the mystery of young Kaspar's incarceration, and the question is more about an essential humanity that can survive mistreatment. Remarkably played by Bruno S, a former mental-hospital inmate, Herzog's Kaspar Hauser is arguably a figure to compare with, say, Greystoke or The Elephant Man: a test case for finding nobility and perfectibility in any human being, or more importantly in the human society in which he finds himself. It is based on the true story of a 16-year-old youth who appeared out of nowhere in a German square in 1828 like an unwanted pet having apparently been imprisoned and beaten as a child, he is all but savage, but nonetheless is taught to speak and reason by kindly townsfolk and briefly taken up by fashionable society. W erner Herzog's captivating The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser, now on re-release, has the elegance and simplicity of a woodcut.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)